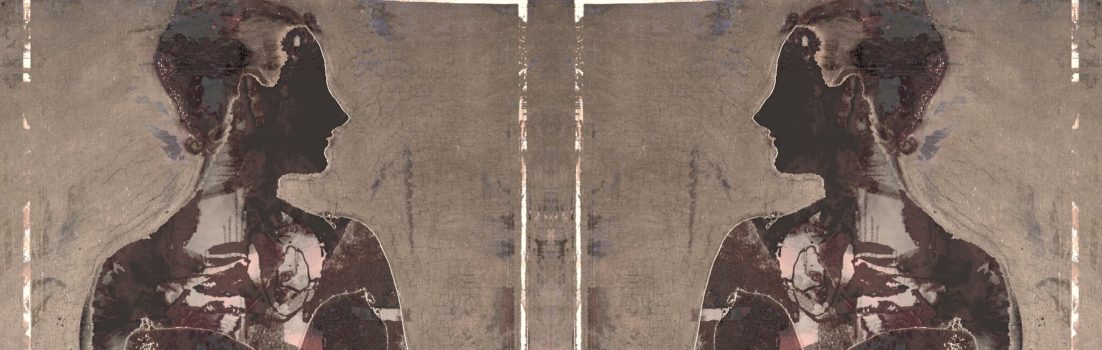

Screen Capture from How To Make Lemonade that depicts paintings of free women of color in tignons

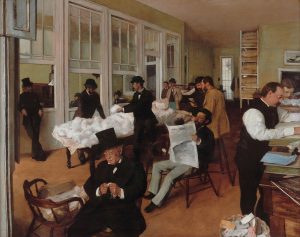

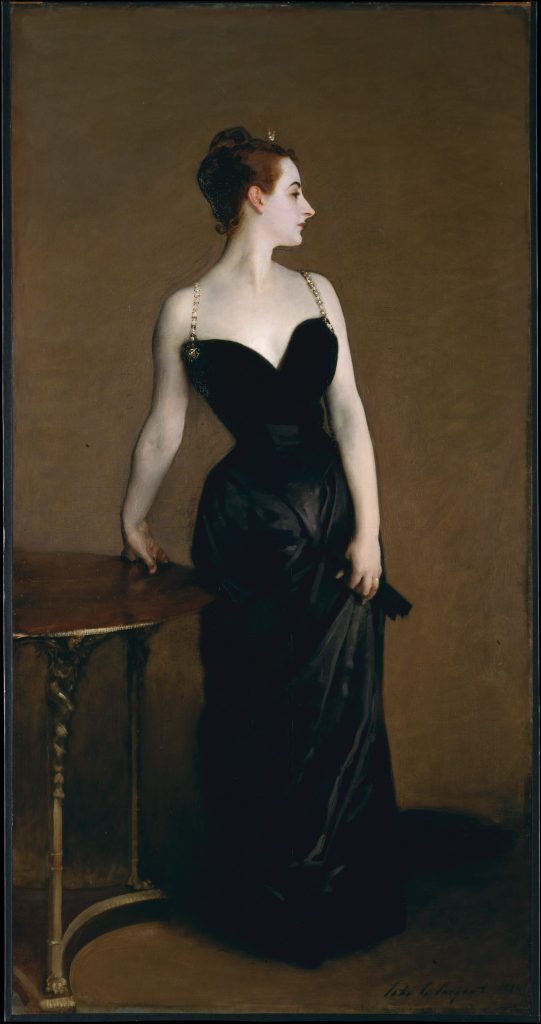

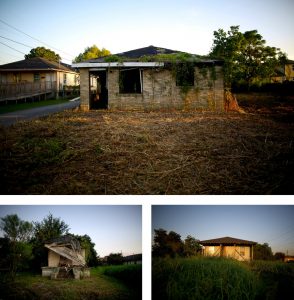

Unfathomable City: A New Orleans Atlas makes it a point very early on to highlight the unique ways in which the city and its residents are at once separated by distinct cultural and geographical markers and pushed together due to lack of land and the very human tendency to commune and exchange culture. In the 1700s, racial, religious, and economic segregation stemming from early immigration, slavery, and the ever-present class divides of an ever-evolving city created a society that simultaneously seems cavalier in its racial mixing and archaic in it its laws and resulting subjugation of the products of it. Gens de couleur libres (free people of color) occupied a space between privilege and extreme oppression that meant they adhered to a unique set of laws made, in some cases, to distinguish them from the enslaved Africans they had seemingly transcended and the white New Orleanians that still viewed them as being distinctly “other.” One of these such laws meant to prevent those of African descent, specifically women, from transcending blackness completely were the Tignon laws.

Historic New Orleans Collection.

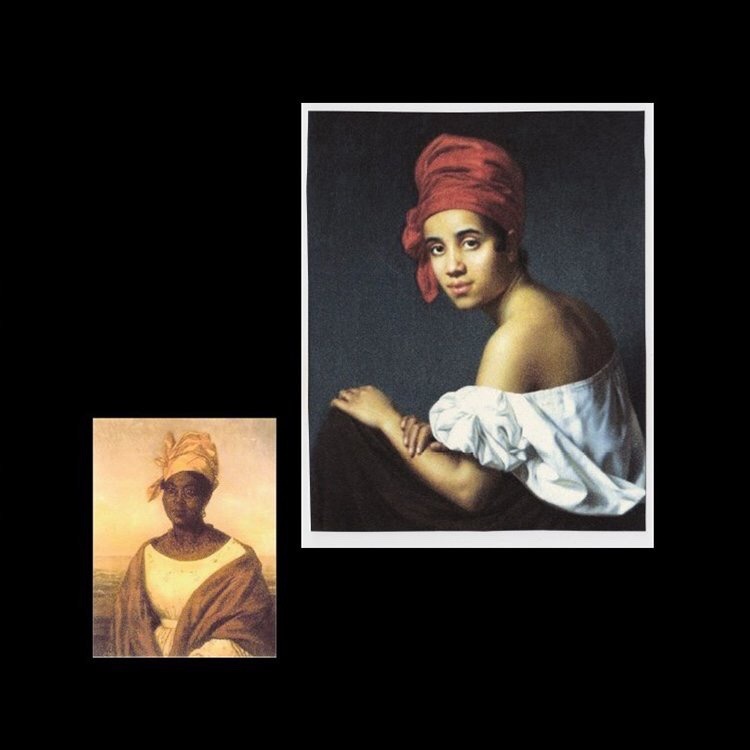

The tignon laws were a set of sumptuary laws (those meant to essentially criminalize decadence and consumption), that were put in place in 1786 under Spanish colonial rule by Governor Esteban Rodriguez Miró. These laws were created to indicate the class status of women of African descent as well as to separate creole woman of color who had achieved a certain economic status and, in some cases, become almost physically indistinguishable from white women. The blurring of class and racial divides not only angered men in power but European women as well, who began to see the highly exoticised Afro-Creole women begin to ascend social strata by marrying into white society or, in other cases, forging economic success of their own. Tignon laws dictated that women of “pure or mixed” African descent could no longer wear their hair uncovered or adorned in public; instead, they must wrap their heads in scarves to prevent “passing” as white or receiving treatment deemed above them. The law also dictated that Creole women of color could not show “excessive attention to dress” in public. The word Tignon itself is a derivative of the French word chignon that translates to “hair bun.” Historian Virginia Gould is quoted in the book Creole: The History and Legacy of Louisiana’s Free People of Color, written by Sybil Klein, as stating that the laws were meant to force free women of color to visually “reestablish their ties to slavery.”

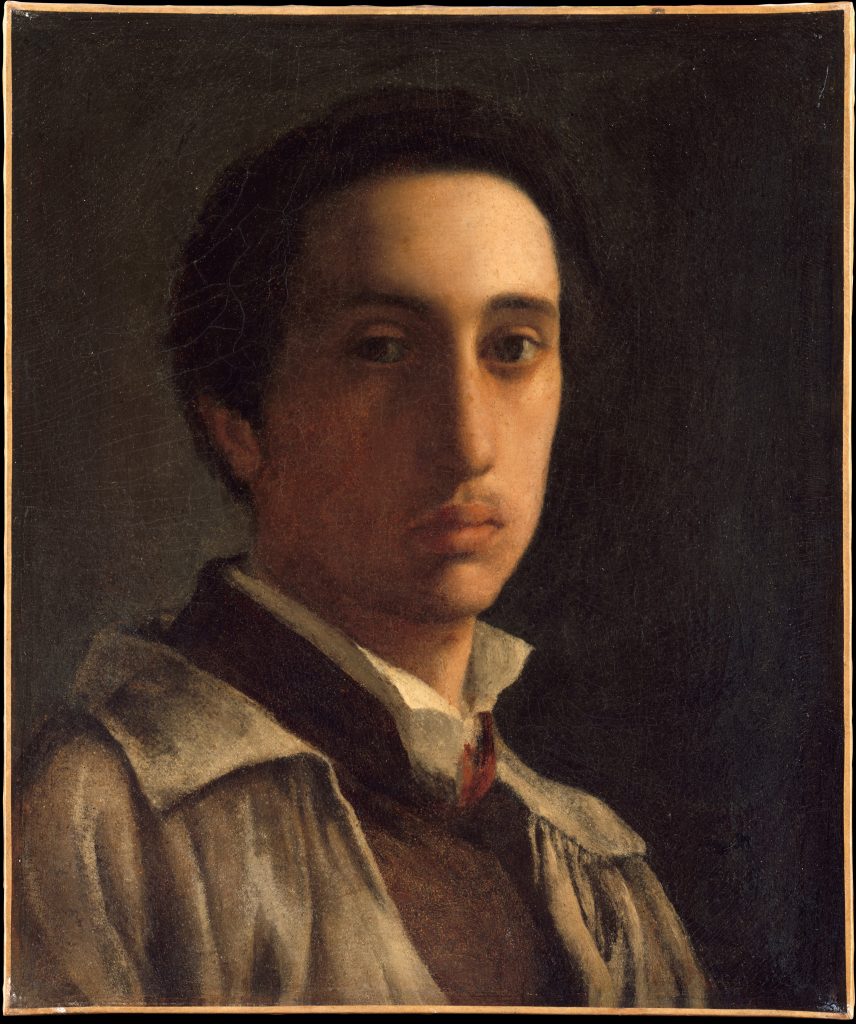

A West Indian Flower Girl and Two Other Free Women of Color

Agostino Brunias

Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

These laws, and the scarves themselves, though meant to subjugate, degrade, and continue the nation’s sordid history of policing black femininity and presentation, were reinterpreted by women of color in extraordinary ways that can still be seen in African-American culture today. Creole women of color who had previously decorated their hair with feathers and jewels did the same with lushly colored scarves that became more of a statement of beauty than a punishment. This form of aesthetic protest became not only a declaration of pride but a positive marker of a culture unique unto itself. In recent years, various interpretations of tignons have experienced a cultural resurgence as women of the African diaspora continue to look to the past and find strength in this unique historical example of ingenuity in the face of institutional debasement.

Screen captures from How to Make Lemonade by Beyoncé

To find out more about the history of the tignon law and Louisiana’s free people of color, click here.

To see a modern interpretation of the tignon, click here.

A popular plant of the South, is the Muscadine. Related to the grapevine, muscadine has berries

A popular plant of the South, is the Muscadine. Related to the grapevine, muscadine has berries

One of Louisiana’s most known flowers, is the Louisiana Iris. It comes in a range of color; from yellow to red, from pink to purple, and from white to blue. The Louisiana Iris (or

One of Louisiana’s most known flowers, is the Louisiana Iris. It comes in a range of color; from yellow to red, from pink to purple, and from white to blue. The Louisiana Iris (or  A wildflower that can also be seen as a common weed is the Queen Anne’s Lace. Often mistaken for yarrow, the clusters of the small white flowers flourish throughout the moist marshlands. This flower has one darker bloom in the center and is a relative of the carrot. As such, it is edible but if eaten is typically consumed while it is younger. Over time, the Queen Anne’s Lace becomes almost wood-like and too tough to consume. The Queen Anne’s Lace is to be harvested with caution, as it closely resembles the deadly hemlock. In turn, too much of the plants’ leaves can prove to make the human body sick. As a result, the Queen Anne’s Lace has been know to have been used as abortifacient throughout history.

A wildflower that can also be seen as a common weed is the Queen Anne’s Lace. Often mistaken for yarrow, the clusters of the small white flowers flourish throughout the moist marshlands. This flower has one darker bloom in the center and is a relative of the carrot. As such, it is edible but if eaten is typically consumed while it is younger. Over time, the Queen Anne’s Lace becomes almost wood-like and too tough to consume. The Queen Anne’s Lace is to be harvested with caution, as it closely resembles the deadly hemlock. In turn, too much of the plants’ leaves can prove to make the human body sick. As a result, the Queen Anne’s Lace has been know to have been used as abortifacient throughout history.

Despite the dangers presented in mustard seed, if it is cultivated correctly, can be used for medicinal purposes in humans. They are rich in minerals, vitamins, and antioxidants. For more information on the health benefits and risks, go to

Despite the dangers presented in mustard seed, if it is cultivated correctly, can be used for medicinal purposes in humans. They are rich in minerals, vitamins, and antioxidants. For more information on the health benefits and risks, go to acters based on real people. During the show’s third season, American Horror Story Coven, the story takes place in modern-day New Orleans. That season featured a few popular New Orleans figures such as

acters based on real people. During the show’s third season, American Horror Story Coven, the story takes place in modern-day New Orleans. That season featured a few popular New Orleans figures such as  s very different. Guests of Lalaurie reported her to be seemingly empathetic and concerned for the well-being of her slaves, while other reports of Lalaurie’s slaves suggested that they were mistreated. As time went on, more rumors spread of the poor treatment of Lalaurie’s slaves. These reports attracted so much attention that her home was visited by a judge to inspect the conditions of the slaves, but nothing was found. Not long after, a neighbor of Lalaurie reported seeing a twelve-year-old slave girl falling from the roof of the Lalaurie home. The neighbor later told a judge that the young girl was running to avoid punishment from Lalaurie. The death of the girl resulted in the Lalaurie family being guilty of illegal cruelty, their punishment being they had to give up nine slaves. Following this, more speculations about what was happening behind the closed doors of the Lalaurie home were made, but no one could possibly imagine what was really going on.

s very different. Guests of Lalaurie reported her to be seemingly empathetic and concerned for the well-being of her slaves, while other reports of Lalaurie’s slaves suggested that they were mistreated. As time went on, more rumors spread of the poor treatment of Lalaurie’s slaves. These reports attracted so much attention that her home was visited by a judge to inspect the conditions of the slaves, but nothing was found. Not long after, a neighbor of Lalaurie reported seeing a twelve-year-old slave girl falling from the roof of the Lalaurie home. The neighbor later told a judge that the young girl was running to avoid punishment from Lalaurie. The death of the girl resulted in the Lalaurie family being guilty of illegal cruelty, their punishment being they had to give up nine slaves. Following this, more speculations about what was happening behind the closed doors of the Lalaurie home were made, but no one could possibly imagine what was really going on. Over time the stories of the ways Lalaurie tortured her slaves became greatly embellished, but it is important to note that we do not know the full extent to which the slaves were tortured. Some of these embellished stories included the slaves having their eyes gouged out, lips sewn together, and intestines pulled out and wrapped around their bodies. Although the most horrific story was Lalaurie’s caterpillar woman where the officials that rescued the slaves found a woman who’s arms were removed and skin peeled off in a pattern to resemble a caterpillar. The horrible reality of Delphine Lalaurie in addition to the intense stories that followed her provided to creators of American Horror Story with a plethora of disturbing material for the show, which they had no issue depicting in the most unimaginable way.

Over time the stories of the ways Lalaurie tortured her slaves became greatly embellished, but it is important to note that we do not know the full extent to which the slaves were tortured. Some of these embellished stories included the slaves having their eyes gouged out, lips sewn together, and intestines pulled out and wrapped around their bodies. Although the most horrific story was Lalaurie’s caterpillar woman where the officials that rescued the slaves found a woman who’s arms were removed and skin peeled off in a pattern to resemble a caterpillar. The horrible reality of Delphine Lalaurie in addition to the intense stories that followed her provided to creators of American Horror Story with a plethora of disturbing material for the show, which they had no issue depicting in the most unimaginable way.

bank of the Mississippi, about 30 leagues below the Huma town. By 1721 not a family was known to exist because the Bayougoula tried to get rid of the Mugulasha after a dispute between the chiefs of the tribes, and after this attempt, the Bayougoula fell victims of a similar event.

bank of the Mississippi, about 30 leagues below the Huma town. By 1721 not a family was known to exist because the Bayougoula tried to get rid of the Mugulasha after a dispute between the chiefs of the tribes, and after this attempt, the Bayougoula fell victims of a similar event.

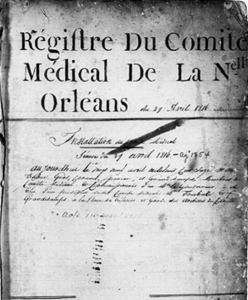

de and population in New Orleans began to increase, the need for healthcare in the city increased as well. The diversity of the population beginning to settle in the city made it so that practitioners of various backgrounds who spoke different languages were necessary to aid the community. In turn, medical societies were formed. The societies were fairly unsuccessful, as practitioners struggled to communicate due to language barriers. Cultural differences led to varying medical opinions on courses of treatment, adding to the difficulty of creating a medical society of practitioners who shared similar ideologies. One of the more successful societies was called The West Feliciana Medical Society. These societies did things similar to that of the current-day American Medical Association, such as establish general standards for ethics, ettiequte, and health. A larger state-wide society was created later in 1878 that led to further advances in medicine, ethics, and ettiequte in the state of Louisiana, replacing the smaller societies mentioned above. This society, the Louisiana State Medical Society, is still in action today.

de and population in New Orleans began to increase, the need for healthcare in the city increased as well. The diversity of the population beginning to settle in the city made it so that practitioners of various backgrounds who spoke different languages were necessary to aid the community. In turn, medical societies were formed. The societies were fairly unsuccessful, as practitioners struggled to communicate due to language barriers. Cultural differences led to varying medical opinions on courses of treatment, adding to the difficulty of creating a medical society of practitioners who shared similar ideologies. One of the more successful societies was called The West Feliciana Medical Society. These societies did things similar to that of the current-day American Medical Association, such as establish general standards for ethics, ettiequte, and health. A larger state-wide society was created later in 1878 that led to further advances in medicine, ethics, and ettiequte in the state of Louisiana, replacing the smaller societies mentioned above. This society, the Louisiana State Medical Society, is still in action today.

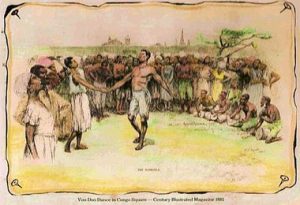

This tradition, originally populated almost entirely by Africans, soon became an attraction for white New Orleans citizens who saw these happenings as a glimpse of Africa and exoticised the intricate drum patterns, dances, religious practices and vocal stylings. Voodoo practitioners such as Marie Laveau often performed altered versions of ceremonies that celebrated African culture although the more closed ceremonies were held privately elsewhere. Congo Square also began to act as a marketplace, allowing the enslaved to experience the economic freedom they hadn’t previously been able to employ. The market gave enslaved Africans the hope of one day being able to buy their freedom in order to the escape the harsh conditions they lived in.

This tradition, originally populated almost entirely by Africans, soon became an attraction for white New Orleans citizens who saw these happenings as a glimpse of Africa and exoticised the intricate drum patterns, dances, religious practices and vocal stylings. Voodoo practitioners such as Marie Laveau often performed altered versions of ceremonies that celebrated African culture although the more closed ceremonies were held privately elsewhere. Congo Square also began to act as a marketplace, allowing the enslaved to experience the economic freedom they hadn’t previously been able to employ. The market gave enslaved Africans the hope of one day being able to buy their freedom in order to the escape the harsh conditions they lived in.

Creole Cottages were some of the first buildings to arise in New Orleans starting in the 1700’s. (

Creole Cottages were some of the first buildings to arise in New Orleans starting in the 1700’s. (

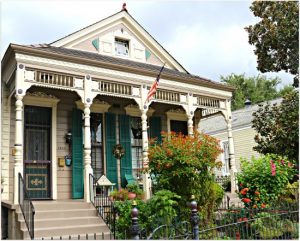

Center Hall Cottages (Raised), or Villas, are typically larger and are placed upon raised foundations. This style of building can be found throughout the South as well as the Caribbean. Typically accompanied by a front porch supported by columns, these houses can be found in a multitude of styles. The most common, are the Greek Revival and Italian Hall Center Cottages, with prominent pillars accenting the house and porches. Queen Anne/Eastlake styles can be found along with other Victorian influenced houses.

Center Hall Cottages (Raised), or Villas, are typically larger and are placed upon raised foundations. This style of building can be found throughout the South as well as the Caribbean. Typically accompanied by a front porch supported by columns, these houses can be found in a multitude of styles. The most common, are the Greek Revival and Italian Hall Center Cottages, with prominent pillars accenting the house and porches. Queen Anne/Eastlake styles can be found along with other Victorian influenced houses. The Shotgun has been thought to have been introduced to New Orleans in the early 19th century. The Shotgun was named so, after the tale that you could shoot a shotgun and the bullet would go straight through the house, and out the other side. The Caribbean style it draws upon is perfect for the damp and marshy environment. It is raised upon stilts (as most homes in New Orleans are), and is a long, narrow structure that makes it inexpensive. As a result, the Shotgun is one of the most common buildings found in New Orleans.

The Shotgun has been thought to have been introduced to New Orleans in the early 19th century. The Shotgun was named so, after the tale that you could shoot a shotgun and the bullet would go straight through the house, and out the other side. The Caribbean style it draws upon is perfect for the damp and marshy environment. It is raised upon stilts (as most homes in New Orleans are), and is a long, narrow structure that makes it inexpensive. As a result, the Shotgun is one of the most common buildings found in New Orleans.

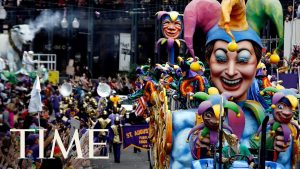

One of the first things that comes to my mind when I think of New Orleans is Mardi Gras. I think of the purple, gold, and green that are shown everywhere. I think of the food and the

One of the first things that comes to my mind when I think of New Orleans is Mardi Gras. I think of the purple, gold, and green that are shown everywhere. I think of the food and the